Chapter One

Chapter One

Chapter One explains how British social life was invigorated through imports of American popular culture in the first half of the 20th century,through mass enthusiasm for American cinema, music and dance. In 1926, for example, 95 per cent of films on British screens were Hollywood productions. Ragtime and jazz were popularised through sheet music and later by gramophones and became a focus for rebellion against Victorian moral values and perceptions of ‘respectability’. Dances like the Charleston and Blackbottom, which enhanced the body’s versatility, allowed young men and women to dance closely and suggestively. Style and design influences can be seen in the take up by amusement arcade and fairground operators of imported American juke boxes.

Chapter Two

Chapter Two

This chapter charts the development of a British juke box industry (based primarily in Blackpool and Ilford, Essex) between 1945 and 1960. Through visual comparisons of juke boxes from the period from both sides of the Atlantic, it illustrates how the fantastically flamboyant American styles of industrial Art Deco and Streamlining scarcely affected British juke box design which developed in its own original and quirky way.

Chapter Three

Chapter Three

Chapter three looks at an orchestrated mediation process that culturally ‘filtered’ American popular music. BBC radio was broadly resistant to musical forms that did not conform to its founding ideals of public education and this meant rock ‘n’ roll. Within the BBC particular fears were raised concerning the effect of mass-cultural broadcasting on Britain’s youth. To simplify the argument, ‘standardised’ or ‘formula’ music (i.e. music produced for a mass-market) was regarded as bad whilst ‘original’ or ‘autonomous’ music was good. General ‘Establishment’ concerns over the perceived subversive ideological affects of hot American jazz were clear. Musical mediation in Britain, however, was not an all-pervading process. Juke boxes were an important catalyst in musical awareness because they disseminated American music by bypassing the BBC’s near monopoly broadcasting position. Juke boxes in this instance played a remarkably similar role to those in pre-war America where juke boxes circumvented racist restrictions imposed by commercial radio stations.

Chapter Four

Chapter Four

Chapter four examines the ‘generation gap’ and the ‘teenage consumer’ who spent money on commodities of ‘no lasting value’ like records, make-up and juke box music. It provides a profile of post-war teenagers and exposes regional differences in youth occupations and culture. Young people’s post-war socialisation was influenced by several key factors like educational opportunity, class structure and an increase in disposable income. The social, economic and cultural conditions surrounding British youth before 1960 influenced teenage receptions of popular culture.

Chapter Five

Chapter Five

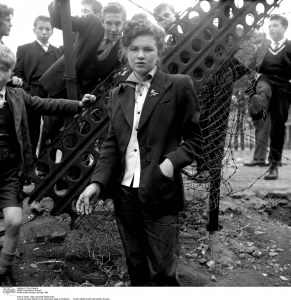

This chapter looks at Teddy Boys, aggression and murder and at the way male youth styles spread after the war. Following a murder from a ‘gang’ stabbing on Clapham Common in 1953 horror and outrage stuck to the Teddy Boy and a media-led moral panic ensued. The flamboyant and challenging Teddy Boy styles of the mid-1950s were nothing new, however. Although highly influenced by America and an upper-class London fashion of the early 1950s, Teddy Boys were part of a continuum of male peacockery that descended from, among others, the London Spiv. Teddy Boy styles and attitudes spread from London to the rest of the country where they fused into regional variations that took on key Teddy Boy signifiers like Tony Curtis haircuts, sideburns, drape jackets or drainpipe trousers. The originally highly distinctive expression of London male youth culture was transformed and diffused into a more mainstream youth fashion.

Chapter Six

Chapter Six

Chapter six looks at young women’s fashions and shows that they were modified through the widespread use of home dressmaking. Fashion influences came from popular culture like magazines and the cinema. Although Teddy Girls did exist, teenage girl’s dress styles were rarely perceived by the public or media as confrontational. ‘Oppositional’ styles did, however, develop at the end of the 1950s. They took on ‘cool’ Continental influences as depicted by Hollywood and the styles of Audrey Hepburn, Leslie Caron and Juliette Greco were highly influential and seen in the jazz clubs.

Chapter Seven

Chapter Seven

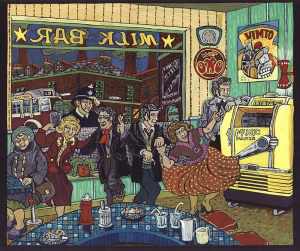

Chapter seven looks at ‘unorganised’ youth venues like coffee, milk, snack and temperance bars and not those organised by well-meaning adults like youth clubs and church organisations. It shows how casual youth meeting places went through a period of change and crossed-over, in parallel with juke boxes, from amusement arcades into small-scale cafes that were rapidly expanding at the time. It assesses the legal implications of relaying recorded music to the public and uncovers an intriguing and complex situation regarding juke box licensing and Copyright Law. Through examining some of the legal material it uncovers ‘Establishment’ attitudes toward popular music like rock ‘n’ roll and the connections that were made between youth, popular music and ‘undesirable elements’. This chapter challenges the idea of a glamorous and flamboyant teenage lifestyle by looking at some of the everyday youth venues of the late 1940s and 1950s. Although unremarkable, these venues provoked an often vociferous reaction by an old-fashioned ‘Establishment’ obsessed with the idea of respectability.